It is always under great difficulties, and very imperfectly, that a country can be governed by foreigners; even when there is no disparity, in habits and ideas, between the rulers and the ruled. Foreigners do not feel with the people. They cannot judge, by the light in which a thing appears to their own minds, or the manner in which it affects their feelings, how it will affect the feelings or appear to the minds of the subject population. What a native of the country, of average practical ability, knows as it were by instinct, they have to learn slowly, and after all imperfectly, by study and experience. The laws, the customs, the social relations, for which they have to legislate, instead of being familiar to them from childhood, are all strange to them. For most of their detailed knowledge they must depend on the information of natives; and it is difficult for them to know whom to trust. They are feared, suspected, probably disliked by the population; seldom sought by them except for interested purposes; and they are prone to think the servilely submissive are the trustworthy. Their danger is of despising the natives; that of the natives is of disbelieving that anything the strangers do can be intended for their good.

- John Stuart Mill, 1861, unintentionally giving advice to the Japanese running the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

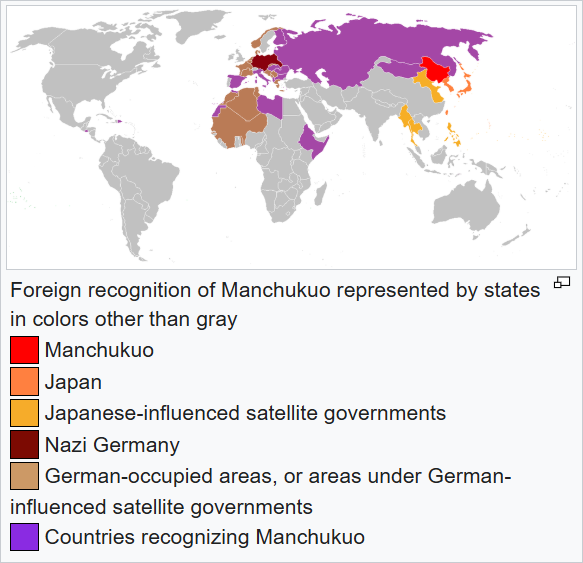

My last post was about the military of Manchukuo, a.k.a. 大滿洲帝國1 The Great Manchurian Empire (1932-1945).

Tonight I realized that Manchukuo was

The Other Reich

because it rose and fell at almost the same time as a certain other Reich. Which happened to recognize it.

However, there were key differences between the two Reichs that went beyond geography and demography. For instance, Manchukuo had a philosophy that at first glance some might call … woke?

Fünf Völker, Ein Reich / Five Peoples, One Empire

The motto of Manchukuo was 五族協和 ‘Concord of Five Peoples’.2 The five were

The Manchus

The Mongols

The Chinese

The Koreans

The Japanese

Each got a color on the national flag.

The five peoples were theoretically all equal under one F-, er, emperor with his own cult.

In May 1938, [the Manchukuo emperor] Puyi was declared a god by the Religions Law, and a cult of emperor-worship very similar to Japan's began with schoolchildren starting their classes by praying to a portrait of the god-emperor while imperial rescripts and the imperial regalia became sacred relics imbued with magical powers by being associated with the God-Emperor.

The religions law built upon the 王道 Royal Way3, the official ideology of Manchukuo devised by Zheng Xiaoxu.4

Andere Völker / Other Peoples

Also theoretically equal to the five - though without representation on the flag - were

The Russians5

The Jews6

The Moslems7

The Oroqen, a sister people of the Manchus

The Hezhen, another sister people of the Manchus

and others I don’t have time to track down.

Manchukuo was supposed to be a showcase for a new, diverse, modern, and even biracial Asia.

The key word in the previous sentence was “supposed”.

Rhetoric vs. Reality

The reality was that Manchukuo had a Manchu ‘emperor’ with no real power because it was a Japanese puppet state run by and for the Japanese. A base of operations against Chinese Nationalists and Communists … and an opium farm.

The Japanese gave opium to the indigenous Oroqen, made them hunt and fight for them, and experimented on them. The Oroqen population plummeted to about a thousand.

Their Hezhen brothers also became addicted to opium and enslaved. Eighty to ninety percent of them died during Manchukuo’s short existence.

I doubt they cared about the Concord of Five Peoples or the Royal Way.

But their Japanese masters, being the most privileged of all, apparently bought into the rhetoric to varying degrees (emphasis mine):

In theory, the Japanese were creating an entirely new, independent state, and this allowed for a considerable level of experimentation regarding the policies that the new state would be carrying out. Many university graduates in Japan who were ostensibly opposed to the social system within Japan itself, instead went to Manchukuo with the belief that they could implement reforms that might later inspire policy within Japan itself.

Compare them to the Manchukuo soldiers who opposed the Japanese government yet ostensibly fought for its puppet Manchukuo.

[…T]he Pan-Asian rhetoric of Manchukuo and the prospect of Japan helping ordinary people in Manchuria greatly appealed to the idealistic youth of Japan. [Louise] Young wrote about the young Japanese people who went to work in Manchukuo: “The men, and in some cases, the women, who answered the call of this land of opportunity, brought with them tremendous drive and ambition. In their efforts to remake their own lives, they remade an empire. They invested it with their preoccupations of modernity and their dreams of a Utopian future.

[…]

[Former Marxist turned Hirohito cultist] Tachibana [Shiraki] went to Manchukuo in 1932, proclaiming that the theory of the “five races” working together was the best solution to Asia's problems and argued in his writings that only Japan could save China from itself, which was a complete change from his previous policies, where he criticized Japan for exploiting China.

[…]

Young also noted—with reference to Lord Acton's dictum that “Absolute power corrupts absolutely”—that for many of the idealistic young Japanese civil servants, who believed that they could affect a “revolution from above” that would make the lives of ordinary people better, that the absolute power that they enjoyed over millions of people “went to their heads”, causing them to behave with abusive arrogance towards the very people that they had gone to Manchukuo to help.

They should have read the John Stuart Mill quotation at the top of this post.

Applicants - possibly mostly Japanese immigrants - had to write (presumably in Japanese) about the Concord of the Five Peoples and the Royal Way in the entrance exam for Manchukuo’s law school (which was run by Japanese). But who knows how sincere their answers were.

What’s perhaps telling is that Carter J. Eckert’s Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866–1945 (2016), largely a study of the Manchurian Military Academy despite its title, does not mention the Royal Way. Eckert gives the impression that cadets and instructors were motivated by the Japanese emperor (while opposing the Japanese government!), Korean and Chinese nationalism, and Communism … but not the defense of Manchukuo, much less its emperor or its supposed ideology.

Eckert only directly refers to the Concord of Five Peoples once (emphasis mine):

Like the new state it served, the Manchukuo Army and its premier training facility were officially committed to a policy of “ethnic harmony,” but as in the Manchurian government administration and bureaucracy, the ideal of “harmony” did not necessarily translate into “equality,” at least in the minds of many Japanese officers and cadets. Although in the army at least rank always took precedence over ethnicity in the chain of command, a Japanese attitude of condescension, sometimes blatant but more often subtle, nevertheless tended to color interethnic relations, exacerbating latent tensions and leading occasionally even to open clashes.

To be fair, the Japanese themselves, or at least the officers and cadets at the MMA [Manchurian Military Academy], were conflicted if not actually confused on this issue. Here the extant diary of one of Park Chung Hee’s [Japanese] classmates, Hosokawa Minoru, is especially revealing. On the one hand, it catalogs countless lectures to the [Japanese] from MMA officials in the corps of cadets to remember and observe the “harmony of the five races” in all their everyday relations with their [Chinese] counterparts. From Superintendent Nagumo on down there was in fact at the MMA a steady clarion call of “[Japanese] and [Chinese] as One,” and section commanders emphasized over and over again that although the [Japanese] were Japanese citizens (kokumin), they were also citizens (kokumin) of Manchukuo and should not let pride in being Japanese turn into a “sense of superiority” (yūetsukan) toward their [Chinese] classmates. They should, rather, in Nagumo’s words, strive for “heart-to-heart, soul-to-soul” relations in all their [Chinese] contacts. Following the outbreak of the Pacific War in 1941, such language took on an even greater urgency, with MMA corps commanders only hours after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor stressing that it was now more important than ever for [Japanese] and [Chinese] to be “of one mind” and for the [Japanese] to “abandon any feelings of superiority.” Many of the [Japanese] cadets, for their part, seem to have made a genuine effort to live up to the ideal of ethnic harmony. Hosokawa, for example, a dutiful cadet with a troubled conscience on this issue, frequently reminded himself that “I love my fatherland [sokoku], but I am also a citizen [kokumin] of Manchukuo” and that “I am in the Manchukuo Army.” He often berated himself for succumbing to the Japanese “sense of superiority,” and whenever he encountered [Chinese] cadets or native Chinese, as he once did on a Sunday excursion to Xinjing [the capital of Manchukuo] to buy souvenirs for his family, he consciously tried to keep in mind the ideal of ethnic harmony.

The problem, however, was that such exhortation and effort toward ethnic harmony existed side by side with contradictory impulses and encouragements. Even though the [Japanese] cadets were formally under the rule of the Manchukuo emperor, many […] thought of themselves as serving primarily the Japanese emperor. And although they served together with [Chinese] officers in the Manchukuo Army, because they were Japanese their role was considered special. Hosokawa had written that “I am in the Manchukuo Army,” but in another entry he also declared, echoing the views of his instructors, that “the Manchukuo Army is the armored train; the track is the Imperial Way8; and the engine is the [Japanese].” What this meant in terms of the [Japanese-Chinese] relationship was that the former had a “duty to lead the [Chinese] like an elder brother [chōkei] and to serve as a model to other peoples.” “We must remember,” Hosokawa noted, that “we have come to Manchuria as messengers of the Japanese emperor to imperialize [kōka]9 a foreign people.”

The [Japanese] cadets’ sense of their special mission, inculcated by their teachers, only strengthened the very feeling of superiority they were being asked to renounce, subverting efforts at ethnic harmony and instead provoking feelings of rivalry or antagonism on both sides. MMA athletic competitions or field exercises thus often simultaneously became ethnic competitions, with the [Japanese] feeling especially disgraced if their prowess and performance did not match their self-image as models and leaders. On a joint [Japanese-Chinese] summer march with heavy backpacks in the Dalian area in 1941, for example, Mitsui Katsuo […] barely managed to avoid passing out from the intense heat. That was embarrassing enough for a cadet whose instructors were constantly telling him that he should be able to surmount all such physical challenges, but as Mitsui wrote later in a memoir, the greater mortification for him would have been for him, a [Japanese], to collapse in the presence of the [Chinese].

Demonstrable evidence of [Chinese] abilities could often evoke a grudging [Japanese] admiration and a resolve to work harder to develop their own strength and stamina to a “superior” level, even in such activities as skating, where, as Hosokawa wrote, the [Chinese accustomed to Manchurian colder weather] were very skilled, “as one might expect.” But the [Japanese] sense of latent, if not always apparent, superiority also led some to act in an arrogant manner toward their non-Japanese peers, especially the Chinese, referring to them even in public […] as “Man-chan,” an infantilizing ethnic slur comparable in English to something like “little Ch!nks.”

Such behavior naturally conspired to make the [Chinese] feel that there was a certain hollowness at the core of the vaunted ideal of ethnic harmony. And even when they were not being subjected to offensive language, [Chinese] sensitivities about Japanese discrimination were fueled by other factors as well. One was the MMA’s mess hall policy of regularly serving white rice to the [Japanese] cadets [for their first six months] and the less desirable staple sorghum to the [Chinese] on the assumption that the unfamiliar sorghum would make the [Japanese] sick. […] And for many of the Chinese […] cadets, the memory of Japan’s ruthless and humiliating invasion and occupation of Manchuria only a few years earlier also worked to bolster perceptions of Japanese arrogance and bias and to intensify feelings of resentment.

The [Chinese] gave expression to these perceptions and feelings in a variety of ways. Some simply shrugged them off and moved on with their training. Others vowed to excel in their endeavors, surpassing their Japanese counterparts and thus proving them wrong. But some took a more confrontational stance as well, using their authority of rank to challenge and discipline [Japanese] underclassmen who failed to observe proper military etiquette or who for one reason or another had not performed well in a school activity. And among the Chinese cadets, there were also not a few whose more radical social consciousness and sense of nationalism led them to form links with the Chinese Communist Party.

The small number of Korean cadets in the MMA classes found themselves in an ambiguous and sometimes difficult position, hovering somewhere between the [Chinese] and [Japanese].

I am surprised Eckert does not mention any prejudice toward the nonnative Japanese spoken by the Chinese and Koreans at the MMA.

Were true believers in Manchukuo at the MMA too embarrassed to mention their old stance when Eckert interviewed them long after the state’s demise in 1945?

Hawaii as the New Manchukuo

I conclude with a crazy idea I had tonight.

The USSA could have made Hawaii its Manchukuo, with Whites running the show behind a puppet Hawaiian monarch - and lofty talk about the melting pot of the Pacific.

Why didn’t it?

Manchukuo had multiple officially recognized languages, so I am going to cite Chinese character terms without pronunciations when they represent Manchukuo-related terms that are pronounced differently in different languages.

Whose languages I have studied. So Manchukuo should appeal to me. But read on and you’ll see why it doesn’t.

Why not the 皇道 ‘Imperial Way’? Manchukuo was ruled by an emperor, not a king. But the term 皇道 ‘Imperial Way’ was reserved for the Japanese emperor. Also, 王道 ‘Royal Way’ was a preexisting classical Chinese term predating China’s first emperor: i.e., it was from a time when a king was still the highest title. 皇道 ‘Imperial Way’ contains Chinese roots but was coined in Japan.

Zheng died suddenly two months before the Religions Law was enacted. What did he think of the Religions Law? I don’t think his Japanese masters cared. They may have killed him! (Then again, he was 77 at the time of his death.)

Russians were eligible for the draft, served in the police, and even had their own military school separate from the main academy that I wrote about in my previous post. (I guess asking them to learn Japanese, the language of the Manchurian Military Academy, was a bridge too far.)

I might revise and expand Facebook posts and comments I wrote about Russian fascism in Manchukuo … and Connecticut. I can’t make this stuff up.

I studied Russian as well, so Manchukuo should really be my kind of place, yet … keep reading.

Manchukuo bordered the USSR’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast (indicated in red below).

The Manchukuo government cracked down on anti-Semitic publications. The never-implemented Fugu Plan was to encourage Jewish immigration to Manchukuo - to make it an “Israel in Asia”, in the words of Colonel Yasue Norihiro.

To my surprise, this group “consisted less of Chinese Muslims than of Arabs and Balkan Muslims” according to Thomas David DuBois (2010), citing a 1943 book on Manchukuo law by jurist Chikusa Tatsuo. I’m surprised the group exists at all because Chinese Moslems usually live further westward. What were “Arabs and Balkan Muslims” - Bosnians? Albanians? Pomaks? Greek Moslems? - doing in Manchukuo?

The “Imperial Way” is the way of the Japanese emperor, not the “Royal Way” of the Manchukuo emperor. See endnote 3.

皇化 kōka, literally ‘emperor-change’, refers to making a non-Japanese people into subjects of the Japanese emperor. Once again (see endnotes 3 and 8), ‘imperial’ terminology refers to the Japanese emperor rather than the Manchukuo emperor.

There was this manga, Zipang, about a Japanese destroyer from the early 2000s being transported through time to the Battle of Midway, lots of stuff happen after that and Manchukuo is mentioned and the multiculturalism is part of the events there if i remember correctly, i don't know if it's relevant later because that's about where i stopped reading it back then, it was a good manga, at least up to that point no idea how you finish a story like that :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zipang_(manga)