People who belong to his fourth category of “anti Russian Westerners”:

Todays post is meant for the 4th and smallest group of SMO skeptics (accusing all of them of being anti Russian is going to far) for whom I have some sympathy and consider smart people.

I don’t consider myself “anti Russian” unless “anti Russian” means “anti-SMO” or “anti-Putin regime”. I’m not against Russians or even Russian soldiers.

’s blog is the reason I’m in the fourth category to begin with. I used to read The Saker and Martyanov. I used to think the SMO might actually accomplish something other than death and destruction.As a matter of fact, this 4th category even has fair representation over at Ruriks blog

and unlike the 3 groups to whom I have nothing to say besides snark and berating the 4th are people I actually would like to engage with in good faith. These are people that know that Russia is not a Stalinist/Bolshevik revanchist Imperial power, but a country ran by people no different than those that run the West. This 4th category has sympathy for Russia and Russians but can’t understand at all why Russian Patriots want to fight Ukraine and NATO to the bitter end on the battlefield while their own country is just as occupied by a hostile satrapy.

Dr Livci’s argument can be summed up in one sentence of his:

As long Ukraine exists Russia is in danger.

Ukraine has become an anti-Russia, and Belarus might eventually be next. Rurik explains how:

Simply put: you divide a formally united territory and then set it against itself in a civil war in which you fund both sides so that neither can triumph completely and consolidate power. This is what Ukraine has become for Russia. It is what Belarus will become or Tatarstan or the Caucasus (again) or Tuva (again) in time.

As I see things from Hawaii, Russian patriots are caught between Scylla and Charybdis - between two branches of the same gang. As Dr Livci put it,

Moscow, Kiev, Washington and London are run by the exact same sort of criminals.

And given that such criminals are in charge of the SMO - and want Ukraine to continue to exist1 - how does fighting the SMO for them eliminate the danger to Russia?

If, as Dr Livci writes, “Ukraine is culturally and ethnically Russian clay historically”, how is killing Ukrainians - Russians by another name - good for Russia? It’s not as if every Ukrainian soldier were a Banderite or in Azov.

The real enemies are in Kiev and Moscow, not the battlefield.

The Other MMA

I am reminded of cadets and instructors at the Manchurian Military Academy (MMA)2 in Manchukuo who thought their real enemies were in Tokyo.

The Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo was an example of what we might now call ‘multiculturalism’ - yes, even in the based Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. I should tell the story of early modern multiculti in the greater Japanese Empire on another day.

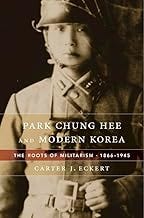

Tonight, I just want to quote Carter J. Eckert’s Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866–1945 (2016) and put three groups in the spotlight:

The Japanese

- and others! - who sympathized with the February 26 coup d’état attempt in Tokyo:

Interviewing former MMA Chinese cadets in Changchun in 1992, I was told that a number of the Japanese officers who had instructed and trained them at [the MMA in] Lalatun in the 1940s were, like Second Lieutenant Yamamoto, filled with admiration for February 26, and that they had openly exhorted their charges, whatever their nationality, to learn from the young officers who had bravely seized the initiative when the Japanese government had been too timid and ineffectual.

To give you an idea of the flavor of February 26, in 1943, Japanese cadets in Japan attended a secret

conference whose themes were “The Anti-Tōjō Movement” and “Down with the Tōjō Cabinet.”

Tōjō Hideki was Japan’s prime minister at the time.

Dr Livci cites musical evidence for his thesis, and Eckert does the same:

Even after February 26, entering cadets at Lalatun [i.e., the MMA] and Zama [i.e., the Imperial Japanese Military Academy] could still find the anthems of May 15 [the assassination of an earlier Japanese prime minister in another military coup d’état attempt] and the Shōwa3 Restoration [the goal of February 26] in their academy songbooks; indeed, both songs continued to be sung openly at the schools through the entire wartime period, as late as August 1945.

tl;dr: They saw themselves as fighting for Japan and its emperor, not Tōjō or his government.

The Koreans

ruled by the Japanese (see Wikipedia for details)

such as Park Chung Hee, born after the annexation [of Korea] in the teens and twenties of the new century, [for whom] the military represented something entirely different from what it had in the past, something more positive and virtuous, a symbol fusing modernity and manhood with national strength and power. Japan had of course used that very strength and power to trample Korean sovereignty three decades earlier, but in the late 1930s and early 1940s imperial Japan was also “at its zenith,” in Kenneth Ruoff’s phrase, seemingly indestructible and growing larger and stronger with each year. For a good number of Korean young men at the time, including even some who would oppose it, the Imperial Japanese Army was also the most visible and palpable incarnation of a martial vigor and power that their parents and teachers had been telling them they needed to cultivate, and toward which they themselves aspired, whether motivated by personal or nationalist desires or by some combination of the two. And now, as its manpower needs multiplied with its expanding wars and territories, the Japanese army for the first time since the annexation had begun to open its military portal to Koreans, including the narrow gate of its officer corps and the institutions that sustained it.

Koreans saw the Japanese military as a means to the end of strength, a principle Rurik would approve of.

Some Korean nationalists, in their own words, “unequivocally support[ed] implementation” of military drills in Korean schools and “persuade[d] Korean young men to join the Japanese army.

And, as T. Fujitani has noted, “extraordinarily large numbers” of Korean young men did in fact apply for military service with the inauguration of a volunteer soldiers program in 1938.

Until 1944, enlistment in the Imperial Japanese Army by ethnic Koreans was voluntary4, and highly competitive. From a 14% acceptance rate in 1938, it dropped to a 2% acceptance rate in 1943 while the raw number of applicants increased from 3000 per annum to 300,000 in just five years during World War II.

Park Chung Hee, my favorite figure in Korean history, was one of those applicants. He and his generation sought strength and in the process made South Korea much stronger.

After the MMA was closed, Park went back to Korea. When he

disembarked at Pusan on May 8 of that year [1946], already eight regiments of a nascent South Korean army had been created under American tutelage, and only seven days earlier a military academy had been established at T’aenŭng in the northeastern part of Seoul on the site of a former Japanese army camp. The Japanese soldiers were of course gone, but within the gates of the new academy and the still untested military units, aspects of IJA [Imperial Japanese Army] culture and practice continued to flourish, and in the after-hours drinking houses patronized by recommissioned Korean officers, one could still hear robust renditions of “Song of the Shōwa Restoration.”

A song of February 26 - to ‘restore’5 the Japanese emperor!

Park’s company of cadets had been heard singing the song in June 1942. They were warned not to let their

“great admiration for the spirit of the young men of [the Japanese coup d’état attempts of] May 15 and February 26” develop to the point of “thinking about destroying the established order” (genjō hakai no shisō).

Park himself would destroy the established order in South Korea when he successfully executed a coup in 1961. On that day, he said,

There is absolutely no other means to save the state and [South Korean] nation.

A means influenced by the Japanese. Park admitted that - speaking in Japanese!

We are young, and from the viewpoint of Japan, what we [South Koreans] are doing must seem naïve, but in fact we are acting in the spirit of the men of high purpose [shishi] of the Meiji Restoration [the successful coup d’etat that inspired February 26]. To that end, we are deeply studying Meiji history.

The Chinese

- also ruled by the Japanese in Manchukuo and in the Japanese colony of Taiwan

who were reading and passing around proscribed books, including original works by Marx.

Some of them

managed to make contact with nearby CCP [Chinese Communist Party] forces while on training exercises in Rehe (Jehol) province and smuggle communist literature back into the academy.

More musical evidence from Eckert:

When the Manchukuo and Japanese national anthems were being played, or when they sang Chinese songs, such as Yue Fei’s “Manjianghong” [Full River Red], that were popular among both the [Chinese] and [Japanese], cadets in the [Chinese secret] societies silently mouthed or focused on alternative lyrics they had memorized denouncing discrimination at the academy or Japanese imperialist political and economic exploitation of Manchuria. They also designated certain words in seemingly innocuous class songs as code terms to subvert or transpose meanings. In one of the MMA 16 [Chinese cadet] songs that railed against Western imperialism, for example, “English and American devils” became code for “Japanese invaders,” so cadets could sing the former loudly and boldly while actually thinking the latter.7 Two MMA 2 songs were composed with similar double meanings, where common phrases such as “fighting for righteousness” were understood as covert expressions of anti-Japanese patriotism.

To no small degree the [Chinese] secret societies owed their survival to the patronage and protection they received from a network of Chinese officers or instructors working at [MMA] itself. The network was extensive. It included section commanders such as Zhang Lianzhi, who composed the two MMA 2 class songs mentioned above, one with the help of MMA 2 cadet Wu Zongfang, who was sent to Zama [the Japanese military academy] with Park Chung Hee and other top-ranked [Chinese cadets] only to defect to the Chinese communists soon after graduation. It also included company commanders with strong communist sympathies [… One] used the time allotted for spiritual or moral lectures (seishin kunwa) to talk about historical materialism, the Soviet revolution, and the CCP.

A Taiwanese cadet

reminded his two [Korean and Chinese] classmates that they should all focus on the [anti-Japanese] struggle that bound Koreans and Chinese together, and the three thereafter became friends.

… while serving the Japanese!

Until August 15, 1945, when the Japanese emperor surrendered. That day,

the five MMA [Chinese] companies who had formed the bulk of the academy’s combat defense unit also mutinied against their Japanese section and company commanders, wounding two in the process, and left the city to join Chiang Kai-shek’s Chinese nationalist forces.

The academic dean of the MMA, Wang Jiashan, had “studied at the IJA Army Staff College in the 1930s” and had seemingly served the Japanese loyally for years. However, he also had founded the secret 眞勇社 Zhēnyǒngshè (True Bravery Society) which

had a strong communist bent from its beginning, but like many patriotic Chinese during this period, Wang looked to both the nationalists and the communists for assistance in his activities, and following Japan’s defeat he initially organized his troops in Manchuria as a provisional division under [Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalists]. But when the Chinese civil war spread to the northeast, he led his entire division over to the communists at the crucial Battle of Yingkou in 1947, thus helping to ensure the CCP’s ultimate victory in that region. Notably, many of the officers under his command at Yingkou were men who had been recruited into the True Bravery Society when they had been cadets at the MMA.

Bottom line: You can’t guess what’s in a soldier’s mind on the basis of his uniform.

I imagine Putin could have taken over Kiev. But he didn’t. His goal is not to eliminate the threat of Ukraine but to stay in power. Rurik explains,

So, the ultimate goal of the wars and the negotiation is to get rid of Putin and his inner circle. Short of that being allowed to occur, Putin is willing to concede almost everything.

[…]

Putin probably just wants guarantees that the Federation will not be dismembered and that his own body won’t be violated while he’s alive either, for that matter.

His FSB goons control and extract wealth out of these federation territories and they don’t want to compete with foreign agencies over the right to parasite off the people. This is their turf, and they’re willing to put up at least token resistance to defend it, as this whole “Not-War in Donbass and Now Southern Russia” kerfuffle has demonstrated.

This is Carter J. Eckert’s short name for the 大滿洲帝國陸軍軍官學校 Dai Manshū Teikoku Rikugun Gunkan Gakkō ‘Great Manchurian Empire Army Officers’ School’. The school had a Japanese name and was run in Japanese by a largely Japanese staff. About a million Japanese had colonized Manchukuo by 1945, comprising about 2.5% of the population; almost all of them went home. A minority made China their new home - and not by choice.

The Great Manchurian Empire was the second and last official name of Manchukuo, whose English name is from a blend of Manchu and 滿洲國 Mǎnzhōuguó ‘Manchurian State’, the Mandarin pronunciation of the original official name.

There were very few actual Manchus in Manchukuo. The puppet state’s supposed emperor Puyi was Manchu - a remnant of the Manchu Qing dynasty that once ruled all of China. But he could not speak his people’s language, despite years of study. He knew more English than Manchu thanks to his English language tutor, Sir Reginald Johnston. After Johnston returned to his native Scotland, Puyi gave him permission to fly the Manchukuo flag on his property.

But Wikipedia also has a table of motivations for Korean enlistment in 1941 including “compulsion”. How would “compulsion” in 1941 differ from the draft of 1944?

It’s not as if the Japanese emperor had lost his throne. “Restore” does not have its normal meaning here. I should write a post to explain it in contexts like this one.

The first class of the MMA. Eckert calls the second class “MMA 2”, the third “MMA 3”, etc.

I imagine that when the Chinese cadets sang in Japanese, the fact that Japanese was not their native language made it easier for them to dissociate the original surface meanings of the lyrics from their new hidden meanings.