My last two posts were about ineffective protests - both online and in the real world.

Standing with Ukraine and Palestine in Paradise

I realize that publicly admitting that I live in Hawaii makes me even easier to dox than I already am. But I can’t resist exploiting my unique vantage point.

As I was wrapping up the second of those posts, I saw this note by

about effective resistance:The preview above cuts off before the lines that leapt out at me:

How to overcome these obstacles then?

My advice: go abroad and organize there first.

That last line brought the title question to mind.

Why Would Hawaii Want a Government in Exile?

tl;dr: Because Hawaii has been occupied by the USSA since 1898. Arguably since 1893, when

United States diplomatic and military personnel conspired with a small group of individuals to overthrow the constitutional government of the Hawaiian Kingdom and prepared to provide for annexation of the Hawaiian Islands to the United States of America, under a treaty of annexation submitted to the United States Senate, on February 15, 1893.

Newly elected U.S. President Grover Cleveland, having received notice that the cause of the so-called revolution derived from illegal intervention by U.S. diplomatic and military personnel, withdrew the treaty of annexation […]

And so the euphemistically named Committee of Safety set up the Provisional Government of Hawaii and, the following year, declared the Republic of Hawaii. Both the provisional government and the republic were never meant to be viable, truly independent states. They were mere placeholders - fig leaves for de facto USSA rule. Which became ‘de jure’1 when

[a]s a result of the Spanish-American War, the United States opted to unilaterally annex the Hawaiian Islands by enacting a congressional joint resolution on July 7, 1898, in order to utilize the Hawaiian Islands as a military base to fight the Spanish in Guam and the Philippines. The United States has remained in the Hawaiian Islands and the Hawaiian Kingdom has since been under prolonged occupation to the present, but its continuity as an independent State remains intact under international law.

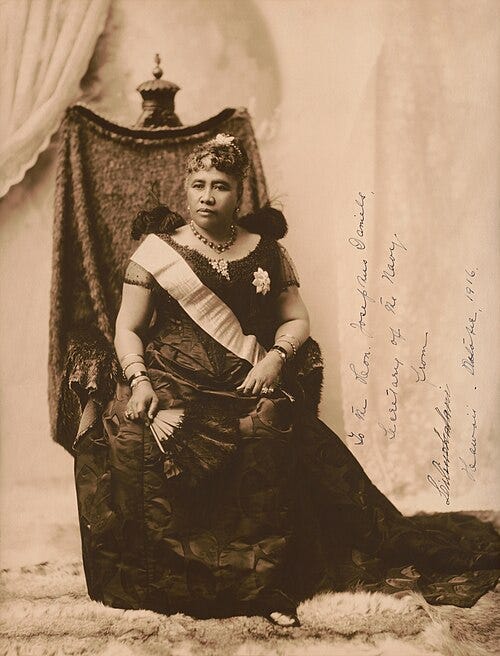

The Queen and the Rebel

In 1895, a rebellion to restore Hawaii’s last monarch, Queen Liliʻuokalani (r. 1891-1893), failed. The queen was arrested, tried, and imprisoned.

She abdicated the throne to save the rebels from execution.

In 1896, she was freed. She spent years in Washington DC in vain seeking the return of the royal lands seized by the USSA. Honolulu Pravda’s ancestor The Pacific Commercial Advertiser wrote in 1903,

There is something pathetic in the appearance of Queen Liliuokalani as a waiting claimant before Congress.

She eventually returned to Hawaii where she received a lifetime pension - a miniscule amount compared to the indemnity she wanted - and died in 1917, almost twenty years after annexation.

One of her last acts was to order the raising of an American flag after five Hawaiian sailors in the USSA Navy had died in World War I. The Outlook, an American magazine, reported the incident in 1917:

Note how the queen was married to an American. That fact is not widely known today. The modern narrative paints the queen as the symbol of Hawaiian nationalism, a victim of the evil racistimperialistcolonialist Americans.

However, the evidence to me suggests a more complex picture - one that does not exonerate the Americans but also does not always flatter the Native Hawaiians. The queen’s deep connections to Whites both before and after the conquest exemplify what I call the Maoli-Haole (Native-White) Alliance that has been almost entirely retconned away. Those connections may have influenced how Native Hawaiians responded to the American takeover.

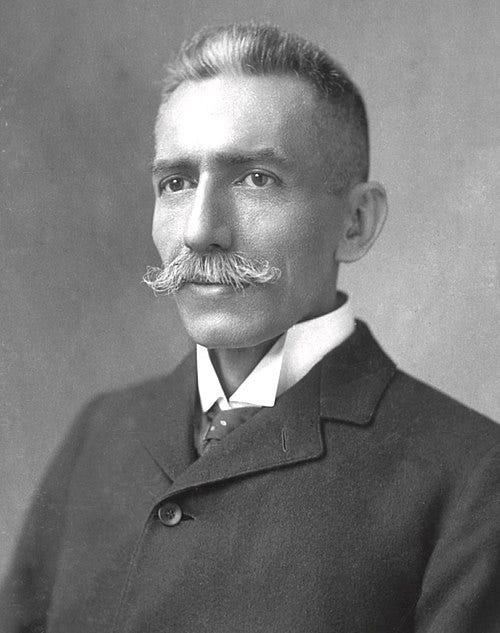

Half-Hawaiian, half-White American Robert William Wilcox, the Iron Duke of Hawaii and the firebrand behind the rebellion of 1895 - and one of the rebels who was saved by the queen’s abdication, became … a delegate to the USSA House of Representatives. A part of the very system that had conquered the kingdom he had fought for. The system from which the queen thought she could get land and money from. Independence? What independence?

If the queen and Wilcox - the apices of late royal-period Hawaiian nationalism - worked within the system, who were the Native Hawaiians who didn’t? Why don’t we hear about them? Because they don’t exist?

And to get back to where I started - why no flowing flight from Hawaii?

The Solar Scenario

In East Asian languages, ‘exile’ is a compound of the roots for ‘flow’ and ‘flee’:

In theory, Native Hawaiian rebels could have fled to the Land of the Rising Sun.

The Hawaiian monarchy’s ties to Japan go back to 1881, when

King Kalakaua [the immediate predecessor of Queen Liliʻuokalani], aged 45, met the Meiji Emperor, who was barely 29 years old, several times during a two-week stay in Japan. The Meiji Emperor “pulled all the stops” for the Hawaiian monarch, including a Japanese Imperial Army band playing “Hawaii Pono,” the Kingdom anthem.

From the Meiji Emperor’s viewpoint, Hawaii was an Asia-Pacific “success story.” When in 1853 Commodore Matthew Perry arrived in Yokohama Bay to pressure the then-ruling Tokugawa warlord to “open” Japan to Western trade and diplomacy, Japan was exposed as a weak feudal state that was defenseless to resist Western industrialized power.

In contrast, in the 1790s Kamehameha the Great deployed state-of-the-art rifles and cannons in amphibious assaults on Maui and Oahu — creating the unified Kingdom of Hawaii; a century later King Kalakaua represented an independent state, not a feudal fiefdom or a colony.

The king wore Western clothes, traveled in steam-powered ships, and knew about the telegraph, photography, and electricity — all startlingly innovative to Japan, which resembled medieval England.

Japan was largely illiterate with only a few temple schools; King Kamehameha the III launched a Kingdom-wide school program in the 1840s, before many European states [or Japan!].

[…]

Since King Kalakaua, who studied military tactics under a Prussian officer, was to Emperor Meiji a “modern” monarch leveraging Western language and education to keep his nation free of Western domination, the emperor changed his meeting schedule to listen to King Kalakaua’s several proposals.

Emperor Meiji viewed Kalakaua as a model of a Westernized, independent Asia-Pacific nation-state.

[…]

In an oft-quoted story, Kalakaua proposed to Emperor Meiji that his 5-year-old [half-Scottish] niece Kaiulani become the bride of Prince Sadamaro, a teen-aged student at the Imperial Naval Academy.

Like a chess player, Kalakaua was thinking several moves ahead when a Hawaii-Japan monarchal linkage may bring Japanese warships to defend the Kingdom against a U.S. marine landing.

That linkage never happened, of course:

However, although the Emperor wanted rapid modernization, an infusion of Hawaiian (and European) blood into the 1,500-year Imperial family line was a stretch for the homogeneous Japanese state.

In 1895, Tōgō Heihachirō, the future architect of victory against Russia in the Battle of Tsushima (1905), commanded the Imperial Japanese Navy cruiser Naniwa which was docked at Pearl Harbor after serving in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) that had ended with Japan’s annexation of Taiwan. This was not Tōgō’s first visit to Hawaii.

Captain Tōgō had previously been a guest of [King] Kalākaua, and returned to Hawaii to denounce the overthrow of Queen Lydia Liliʻuokalani, sister and successor to the late king and conduct “gunboat diplomacy”. Tōgō refused to salute the Provisional Government by not flying the flag of the [Hawaiian] Republic. He refused to recognize the new regime, encouraged the British ship HMS Garnet to do the same and protested the overthrow. The Japanese commissioner eventually stopped Tōgō from continuing his protest, believing it would undo his work at restoring rights to Japanese [in Hawaii; see below]. [Naniwa cadet and future chief of Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff] Katō Kanji wrote in hindsight that he had regretted they had not protested harder and should have recruited the British in the protest.

The continued presence of the Japanese Navy and Japan's opposition to the overthrow [more precisely Tōgō’s opposition] led to a concern that Japan might use military force to restore Liliʻuokalani to her throne as a Japanese puppet. Anti-Japanese sentiment heightened.

At least two very prominent Japanese had respect for the Hawaiian monarchy. What if the queen had gone into exile in Japan instead of heading for Massachusetts once she was released?

Đông Du

Why didn’t young Hawaiians follow the example of the Vietnamese? Their Đông Du ‘Eastern Travel’ movement

at the start of the 20th century […] encouraged young Vietnamese to go east to Japan to study, in the hope of training a new era of revolutionary independent activists to rise against French colonial rule[.]

The answer, I strongly suspect, lay in a lack of … affinity between Native Hawaiians and Japanese.

Vietnamese revolutionary Phan Bội Châu

asked [former Japanese prime minister] Okuma for financial assistance to fund the activities of Vietnamese revolutionaries. In his letter to Okuma, Phan stated that Japan should be obligated to help Vietnam since both countries were of the "same race, same culture, and same continent".

Proving Phan’s point, Phan probably wrote his letter in classical Chinese, assuming that Okuma would be able to read it without translation. Educated men throughout East Asia at the time could all read and write classical Chinese.

Native Hawaiians could not claim to be part of the Sinosphere. Nor might they even want to, because the Maoli-Haole Alliance had oriented them toward the West. Native Hawaiians at the time (certainly not anymore!) looked up to White Christians and looked down on the Japanese in Hawaii who were merely cheap imported labor. In the last days of the Hawaiian Kingdom and under the following interim governments, the Japanese and other Asians in Hawaii could not vote or become citizens unlike Whites. That has been totally forgotten in today’s POC-versus-White paradigm. But it was on the mind of the Japanese commissioner in Hawaii who told Tōgō to knock off his protest, lest it impede efforts to obtain more rights for the Japanese.2

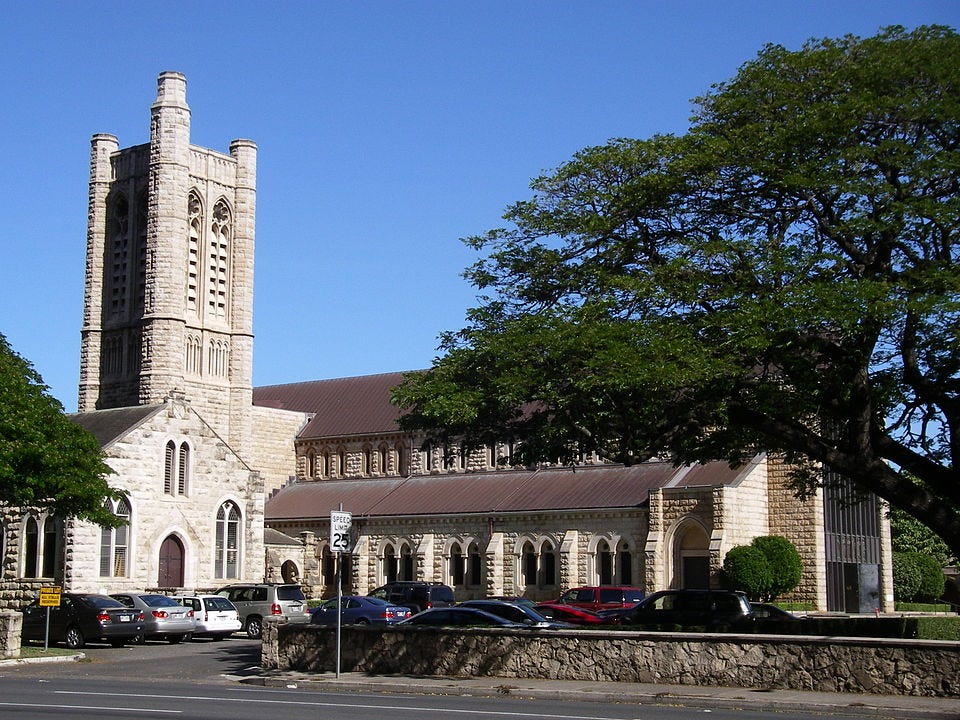

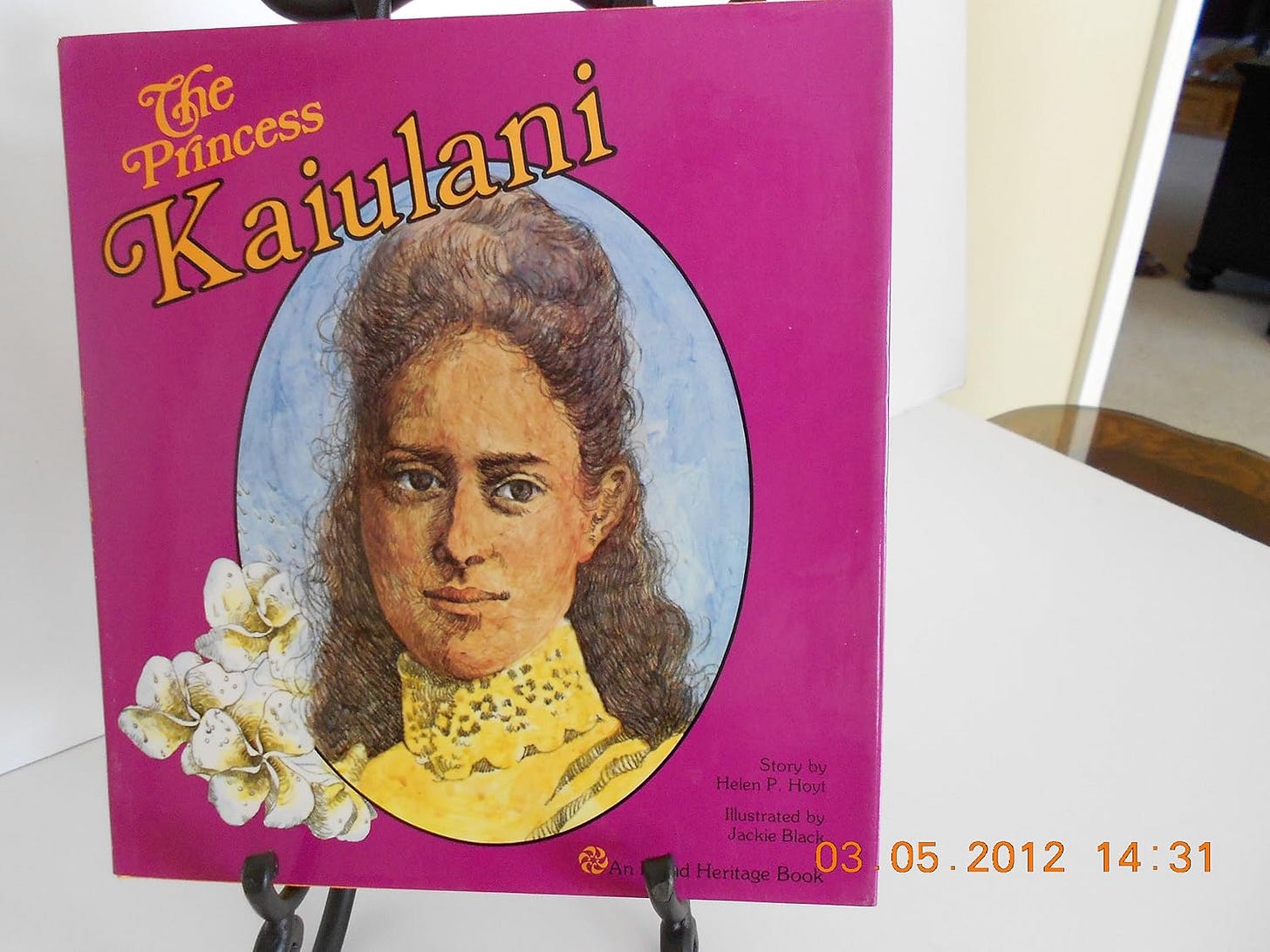

Remember half-Scottish Princess Kaʻiulani, whom King Kalākaua wanted to marry into the Japanese imperial family? She was christened at an Anglican cathedral commissioned by Kamehameha IV (guess the royal family’s religion!) and taught by British, American, French, and German governesses before studying in England.

After the fall of her kingdom,

she [Princess Kaʻiulani] and her father assumed the lives of itinerant aristocrats traveling across Europe and the British Isles. They stayed in the French Riviera, Paris, and on the island of Jersey, as well as England, and Scotland.

[…]

As her funding ran out, she wondered if the Provisional Government would give her an allowance.

That wasn’t mentioned in the 1974 biography of the princess that I read as a child half a century ago.

Then and now, she is viewed as a tragic figure - the princess who never got to ascend the throne. She does not seem to have been much of a nationalist. What nationalist royal would want an allowance from the conquerors of the territory that should have been theirs?

No Hawaiian Ho

In theory nonroyal Native Hawaiians could have also gone abroad for the cause of independence, but I am unaware of any. There was no Hawaiian Ho Chi Minh, who

worked in various countries overseas, and in 1920 was a founding member of the French Communist Party in Paris. After studying in Moscow, Hồ founded the Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth League in 1925, which he transformed into the Indochinese Communist Party in 1930. On his return to Vietnam in 1941, he founded and led the Việt Minh independence movement against the Japanese, and in 1945 led the August Revolution against the monarchy and proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. After the French returned to power, Hồ's government retreated to the countryside and initiated guerrilla warfare from 1946.

And we know the rest of the story.

I have a lot of other stories to tell about exiles, but (1) they’re not Hawaii-related, (2) I’m out of time, and (3) this post is already a day late, so watch for a sequel.

The annexation isn’t legal according to Hawaiian sovereignty activists, of course. I myself don’t believe in laws. But I do think the de facto/de jure distinction is convenient shorthand for differentiating between the 1893 American takeover in all but name and the 1898 formalization of the land grab.

Rights that the Japanese born in Hawaii after April 30, 1900, obtained when they became American citizens at birth.